nitinaht

hishuk Ish ts'awalk

everything is one

[/et_pb_popup_builder]

Our history & culture

We have gained an understanding of our past; we know our territory and the history associated with this land, and we are ready to share it with others.

Our territory

Our Ditidaht territory is large. It stretches inland to include Cowichan Lake. It reaches down Nitinaht Lake and deep into the forests. It extends along the coast between Bonilla Point and Pachena Point and encompasses a considerable distance offshore.

On the other side of Bonilla Point live our close relatives, the Pacheenaht, and to the northwest of Pachena Point is the country of our neighbours the Ohiaht who speak a different language.

More generally, Ditidaht territory on land extends to the headwaters of the streams and rivers which drain down to the coastline. Ditidaht territory extends out to sea and includes the rich salmon, halibut and cod banks that feed our people.

Ours is a big country that is rich in the foods we like to eat. Every year the salmon come back to rivers like the Cheewhat, Hobarton and Nitinaht. We can always get mussels from the rocky coastline and sea urchins in the shallow waters. And there are thousands of crabs scurrying around the lower end of Nitinaht Lake, just waiting to be trapped. Deer and elk are in the forests and berries of all types are growing on the hillsides. Ducks are everywhere. People never go hungry in Ditidaht country!

Oral tradition indicates that at one time–some say this was before the Great Flood–the da7uu7aa7tx, the original Nitinaht people–lived in the Nitinaht Lake area. These da7uu7aa7tx people were joined later by the diitiid7aa7tx, the people who had come from Tatoosh Island across the Strait of Juan De Fuca and established a settlement at Jordan River. Indeed, the Nitinaht Indian term for Jordan River is diitiida; those who established the village at Jordan River were called diitiid7aa7tx, which means ‘diitiida people.’ This term, diitiid7aa7tx, is anglicized as “Ditidaht.” That is why we are called “Ditidaht” (“dee-tee-daht”), which is often pronounced “Nitinaht.” “Nitinaht” is a “Westcoastized” pronunciation of diitiid7aa7tx, as “d” in Nitinaht is pronounced “n” in Westcoast (formerly called “Nootka”), the language spoken between Pachena Point and Cape Cook.

Boundaries between territories were looked upon very seriously by the old-time Ditidaht and their neighbours. Sometimes these boundaries were noted by large boulders on the beach or by points of land; the people told stories relating how major disagreements erupted when valuable items drifted in from sea and settled on a boundary, and how occasionally, boundary disputes were resolved by holding jumping contests.

Our knowledge of our boundaries is retained in oral tradition. Some of our stories talk about the time before the Whiteman arrived on the coast, when there were many more people defending their villages and salmon streams. Villages were raided, people were killed, and some groups became extinct. This situation continued well into the 1800s, resulting in a great deal of change in territories as groups disappeared or amalgamated with others.

Amalgamation of small groups and relocation of some villages has caused some confusion in what is Ditidaht territory and what belongs to our neighbours. To sort out such problems we have turned to our elders, the tradition-bearers of our history. They have told us their stories, translated stories recorded by past generations of elders, and importantly, have considered the diversity of opinion that results from history’s oral transmission.

We have also searched archives for early reports on our people and their whereabouts. Dr. Robert Brown who stated the following on the basis of his extensive explorations of this region in 1864 made one of the earliest statements about the boundaries of Ditidaht territory:

They [the Ditidaht] have–or had–many villages, from Pachena Bay to the west and Karleit [kalaayit, just east of Bonilla Point] to the east, besides three villages in Nettinaht Inlet, eleven fishing stations on the Nettinaht River, three stations on the Cowitchan Lake, and one at Sguitz [Skutz Falls] on the Cowitchan River itself.

We have gained an understanding of our past; we know our territory and the history associated with this land, and we are ready to share it with others.

Early population

One of the earliest references to Indian people in the present study area appears in an 1849 report written by W.C. Grant for Governor James Douglas. Grant settled in the Sooke area that same year. Nitinaht-speaking Indians employed by Grant told him that the “Natives around Patchana…or Pt. San Juan…are numerous, those at Nittinat [Nitinat Lake area] still more so.” No actual estimates of the numbers of Ditidaht or Pacheenaht were given at this time.

James Douglas compiled a census in 1853, based on data obtained in previous years from various sources. In the Douglas census, the Indians of this region were identified only as “Netenet” [Nitinaht] and their place of habitation was identified only as “Point San Juan” [presumably, Port San Juan]. This “Netenet” census enumerated 250 “Men with Beards,” 258 women, 29 boys, and 2 girls, totalling 539.

Two years after this Douglas census, additional data were provided by Peter Francis and W.E. Banfield. In a letter written to Governor Douglas in July 1855, Francis and Banfield said they had been trading with Indians for the past 12 months along the west coast of Vancouver Island. They estimated the total population of the “Nettinets” to be 800 including men, women, and children. Of this population, 250 were said to be “able bodied men.”

In 1858, Banfield identified the “Pachinett” as “a branch of the Netinett tribe.” He said the Nitinahts lived between “Ohiat head” [Cape Beale, west from Pachena Point and Pachena Bay] and Port San Juan. Banfield stated there were “about five hundred” Nitinahts but only “about twenty” Pacheenahts living at Port San Juan. A separate Banfield census, likely made in 1858 or 1859, stated this figure of 20 Pacheenahts referred only to adult males, representing one third of the population. Similarly, a figure of 200 Nitinahts given in this same census was also said to be one third of the population. This suggests, for the late 1850s, a Ditidaht population of 600 and a Pacheenaht population of 60. Robert Brown stated that in 1863-1864, the “Nettinahts…had four hundred fighting men” and added that “a few years earlier they were estimated at a thousand.” Brown distinguished the “Nettinahts” from the “Pachenats” whose population in 1863, he stated, “did not exceed sixty.”

Indian Affairs records beginning in the early 1880s provide additional estimates of the Ditidaht population. Harry Guillod, Indian Agent for the west coast of Vancouver Island, reported that when he took a census in the summer of 1881, there were “90 Nitinat men” of a total population of 280 Nitinats “living in four rancheries [settlements] between Cape Beale and Pacheena” [Port San Juan]. Guillod identified the “Pacheena” [Pacheenaht] Indians separately. Subsequent estimates of the Ditidaht population included totals of 271 in 1883, and 220 in 1889. In a census prepared in 1914 for the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs, 40 Ditidaht families were enumerated, with a total population of 155.

The present-day Ditidaht Nation population is about 350, of whom approximately 120 live on our Malachan Indian Reserve at Nitinat Lake. We maintain an elementary school for our younger children and offer them instruction in Ditidaht language and culture. We are preparing curriculum materials to teach our children their history.

Establishment of reserves

The earliest Indian administration in British Columbia was undertaken by Hudson`s Bay Company officers and James Douglas, who as Chief Factor at Fort Victoria from 1849 to 1858 (and as Governor of Vancouver Island from 1851 to 1864), gained a reputation for efficient and impartial dealings with Indians and non-Indians. Douglas believed that aboriginal people’s rights would be protected by negotiating “treaties” with the various tribes. Before he could complete this task, he ran into obstacles: not enough money, and not enough support from other government officials.

Thus, the Ditidaht did not sign a treaty. Nor were any of our lands set aside as Indian Reserves during the Colonial period. It was not until the establishment of the Joint Indian Reserve Commission that the Commissioners came to our territory. In 1890, the Commissioners met with our Chiefs and decided upon seventeen pieces of land which were to be allotted as Indian Reserves. These were the villages where our people lived and the camps where they fished for salmon and halibut and constructed canoes. By no means were these all of the places where these activities occurred; yet Indian Reserves did provide protection to several significant residential and resource sites.

The seventeen Indian Reserves (excluding the cemetery) that were established are as follows:

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 1

This reserve is named 7a7ukw which means ‘lake.’ It is called “Ah-uk” Indian Reserve No. 1 and is located on the east side of Tsusiat Lake. There was one house here in 1892 when the surveyors marked out this reserve of about 130 acres.

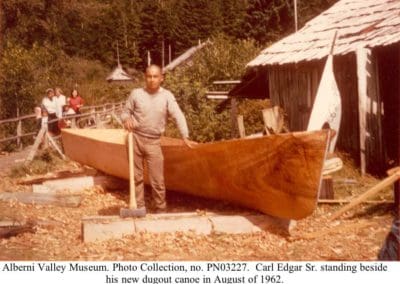

This place, 7a7ukw, was a well-known area where our people carved dugout canoes. The red cedar growing here was particularly good for canoe making. The people lived at 7a7ukw while making canoes but they did not stay here all the time. This was a camping area.

The canoes made up at 7a7ukw were brought down to the ocean in two special ways. Carl Edgar and his brother, the late Martin Edgar, remembered one method: they were told that Ditidaht people lowered the canoes on ropes down alongside Tsusiat Falls. Joe Edgar talked about how some people slid their canoes down a canoe run between the bottom end of Tsusiat Lake and the beach on the west side of “Hole Point” (Tsusiat Point).

There used to be a trail that connected 7a7ukw with “the Flats” which is our Indian Reserve No. 7 at the southwest end of Nitinat Lake.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 2

This place is called tsuxwkwaada. It is known as “Tsu-qua-nah” Indian Reserve No. 2 and is located on the ocean. It is west from the entrance to Nitinat Narrows. A long time ago, there used to be a large Ditidaht village at tsuxwkwaada. The late Joshua Edgar used to say that the people who lived here were known as strong and fierce warriors. People up and down the coast were afraid of them! This village was also a place where the people lived when they went out halibut fishing and fur seal hunting. As well, whales were towed to this village after they had been harpooned by our whale hunters.

There were five houses at tsuxwkwaada when the surveyors marked out the 235-acre reserve here in 1892. In 1901, 25 people were living here in four houses. But by 1914, there were only three houses at tsuxwkwaada.

The late Martin Charles remembered going to tsuxwkwaada when he was very young. He went with Old George Gibbs who had a house there. He remembered the old man catching halibut so large that one fish could fill a canoe!

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 3

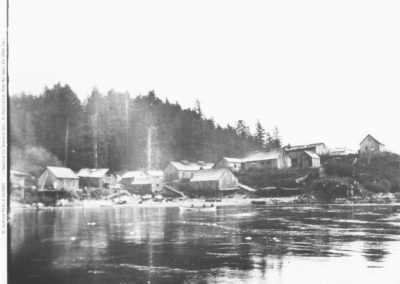

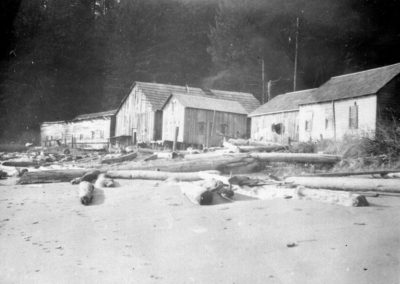

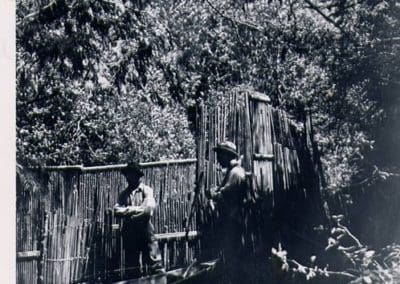

This reserve is called waayaa which means ‘high place.’ It is located on a high bluff at the entrance to Nitinat Narrows. Ditidaht people often refer to this place as “Nitinat” or “Whyac.” The elders like to call it by its real name, waayaa.

Waayaa was the main Ditidaht village for many years. It was so large, that the houses here were right next to one another. They were so close that you could hear your neighbours talking in their house next door! People lived here until the 1960s when they moved to Malachan. There are still a couple of old houses at Whyac, although they are overgrown with salmonberry bushes. But when the 132-acre “Whyac” Indian Reserve No. 3 was surveyed in 1892, there were many houses here. In 1901, there were sixty-three Ditidaht people living in twelve houses at waayaa and in 1914, there were fourteen houses here. At least fifteen houses were here in the 1930s.

Many of our families lived at waayaa at one time or another. Some of the people who lived here in the 1930s were: the late Martin Charles, Mary Thompson, Dan Daniels, Harry Joseph, Gallic Dick, Old George Gibbs, Bobby Joseph, Ernest Johnson, Joe Shaw, Walter Shaw, and Mack Robinson.

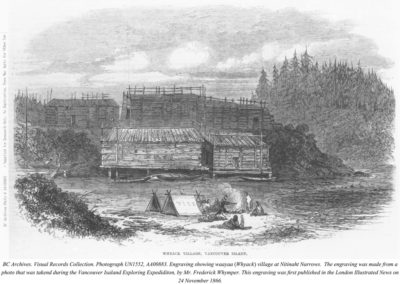

In earlier times, a stockade was built around the village of waayaa. This was to protect the village from attack by our enemies. In 1864, some explorers led by Doctor Robert Brown made a visit to our village of waayaa and saw this stockade. It impressed one of the explorers so much that he drew a picture of it. Dr. Brown described the village this way:

Most of the Nitinaht villages were fortified with wooden pickets to prevent any night attack, and from its situation, Whyac, the principal one (built on a cliff, stockaded on the seaward side, and reached only by a narrow entrance where the surf breaks continuously), is impregnable to hostile canoemen.

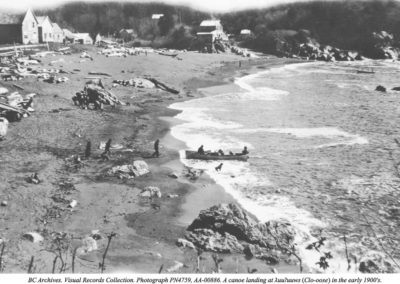

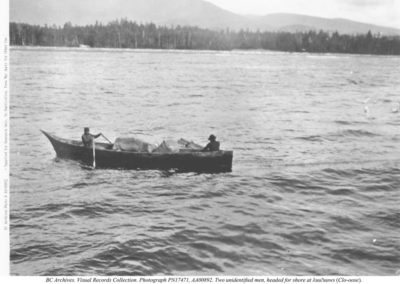

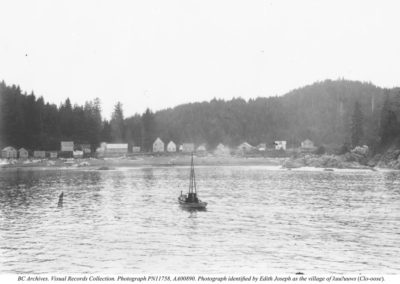

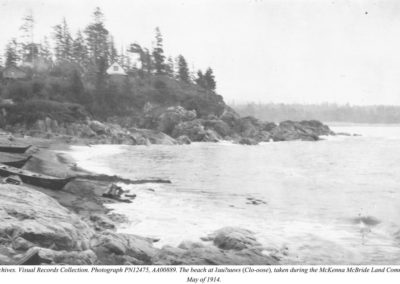

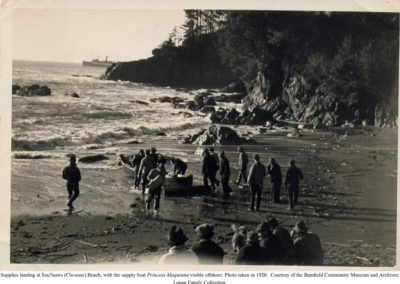

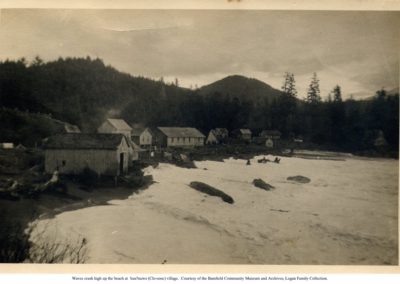

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 4

The name tluu7uus, meaning ‘camping place,’ refers to “Clo-oose” Indian Reserve No. 4. It is located on the ocean east from the entrance to Nitinat Narrows. Tluu7uus was an important Ditidaht village. Lots of fish and beach-foods were obtained near here. People continued living at tluu7uus until the 1960s, just as they did at Whyac. Many of our people still go here to camp in the summer time, simply because it is so beautiful and quiet.

There were seven houses at Clo-oose when the 237-acre Indian Reserve was surveyed here in 1892. By 1901, there were fifteen houses at tluu7uus, and 69 people lived here. In 1914, there were sixteen houses at Clo-oose, and in the 1930s there were about twenty houses here.

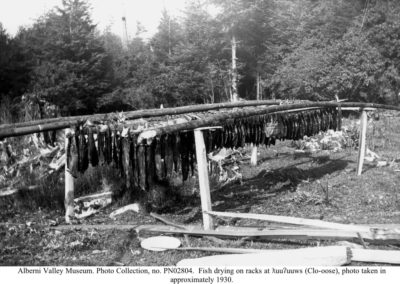

The late John Thomas explained how the people living at tluu7uus in the early days used fish weirs and traps. A weir is like a fence that goes across the stream and stops the salmon. They placed these in the Cheewhat River nearby so that they could catch salmon. You can still see the remains of these fish weirs in the Cheewhat River today.

Some of the people who had houses at Clo-oose in the 1930s were: James Thomas, Leo Thomas, Henry Tate, the late Joshua Edgar, the late Effie Tate, Gillette Chipps, William Jackson, George Robertson, Nichol Chester, Mabel Shields, and Annie Lazar.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 4a

This reserve is a 9-acre Ditidaht cemetery on the located on the east side of the Cheewhat River mouth. The cemetery is known as tlaasabaks which means ‘temporarily set on the beach.’ It takes its name from the sandbar that extends out from the shore here. Small trees grow on this sandbar every year but are washed away in the big winter storms. That is why the trees are only temporary.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 5

Ts’a7akwuu means ‘side creek.’ It is the name of “Sarque” Indian Reserve No. 5 located alongside the upper Cheewhat River. This was another place where the Ditidaht people obtained salmon. The 1892 survey of this 26-acre reserve shows a house and a fish weir here.

Tom tl’iishal, who was Ida Mills great-grandfather, once had a house here at ts’a7akwuu. He had a fish weir and trap in the river where he caught salmon. Another man who had a house here was Henry Chipps.

The Ditidaht people obtained cedar bark and spruce roots up the Cheewhat River. They also got red cedar for canoes here, and yew wood for making bows. As well, the people picked blueberries and huckleberries in the upper Cheewhat area and dug edible roots known as tlitsapt.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 6

Kwaabaaduwa7 meaning ‘as far up as a canoe can go,’ is the name of “Carmanah” Indian Reserve No. 6. It is located on the ocean west from the mouth of Carmanah Creek. It is hard to land a canoe here in rough weather, but there are certain spots on the beach where it is safe to go.

This was a Ditidaht village where people lived during the halibut season. People also lived at Carmanah year-round. There were three houses at this 158-acre Indian reserve in 1892, and in 1901, 51 people lived in eight houses here. There were six houses at Carmanah in 1914.

The last people who lived year-round at kwaabaaduwa7 were members of the Knighton family; this was in the 1920s. Ditidaht people continued going to Carmanah in the summertime during the 1930s and 1940s. A few families still like to camp here.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 7

This place, known as “the Flats,” is located at the southwest end of Nitinat Lake. It is known as “Ik-tuk-sa-suk” Indian Reserve No. 7. The Ditidaht name for this reserve is hitats’aasak which means ‘inside area.’ It was named this because the village is just inside the Narrows. This same place is also known as da7uua.

It is said that at one time there was a very large village here at hitats’aasak and that those who lived here were our original people. These original people were called da7uua. Later they became known as “Ditidaht.”

A long time ago, hitats’aasak was an important winter village for the Ditidaht people. It was also an area where salmon were caught and smoke-dried. Salmon are still caught near here today. In the fall time, you can see hundreds of salmon in the lake offshore from the reserve. Some of our fathers and grandfathers set nets here and then bring the salmon home to Malachan to be cut up.

There were seven houses at “the Flats” in 1892 when this 168-acre Indian reserve was surveyed. In 1914, there were six houses here. Among those people who used to live at “the Flats” were Henry Tate, Philip Joseph, Sam Williams, Alfred Livingstone, Old George Gibbs, Police Charlie, and George Robinson.

Today there are three houses at hitats’aasak; one of them belongs to Mike Thompson, another was owned by the late Martin Edgar, and the third is a float-house belonging to Carl Edgar, Senior.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 8

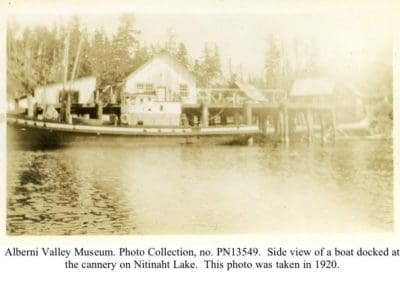

This place is known as “Hobarton.” Its Ditidaht name is xwubit’ad which means ‘snoring sound made by rushing water.’ “Ho-mit-an” Indian Reserve No. 8 is located at the mouth of Hobiton Creek on the west side of upper Nitinat Lake.

Hobarton was a well-known place to catch and smoke sockeye salmon. People stayed here during the fishing season. In the old days, our people used fish traps to catch the salmon in Hobiton Creek. Sockeye salmon are still caught at Hobarton today.

There were four houses at xwubit’ad when the 50-acre Indian reserve was surveyed here in 1893. There was one house here in 1914. Today the Ditidaht Band has a fisheries building at Hobarton, and our Fisheries Officer, Sam Edgar, stays here sometimes. Among those who used to have houses at Hobarton were the late Joshua Edgar, Peter Dick, Old George Gibbs, Harry Joseph, and the late Martin Edgar.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 9

The name of this place is uuyiyi7s which means ‘part way down the lake.’ It is known as “Oyees” Indian Reserve No. 9 and is located on the east side of lower Nitinat Lake. There was one house at uuyiyi7s when the 104-acre Indian Reserve was surveyed here in 1893.

“Oyees” was a well-known place for making dugout canoes as there were excellent red cedar trees in this area. The people used to camp here while making canoes. They also obtained cedar bark here and cedar planks for making houses. As well, salmon were caught here.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 10

“Duba” meaning ‘taboo place’ is the name of “Doo-bah” Indian Reserve No. 10. It is located on the east side of the centre portion of Nitinat Lake. There was one house here when this 13-acre reserve was surveyed in 1893.

This was a place where people caught and smoke-dried dog salmon. They camped here at “Doo-bah” during the fishing season. Jimmy Smith used to have a smokehouse here. Red cedar for canoes and house planks was also obtained at duba, as the cedar in this area is very good.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 11

“Malachan” Indian Reserve No. 11 is known as balaats’adt . It is on the east side of the upper end of Nitinat Lake, near the mouth of Caycuse River. A long time ago, people stayed at Malachan only during the fishing season. The Ditidaht used to fish at night for dog salmon and hunt ducks off from balaats’adt using the light from pitch torches.

There were two houses at balaats’adt when the 66-acre Indian Reserve was surveyed here in 1893; there was one house here in 1914. This house was owned by Molly Chipps who was Frances Edgar’s mother.

Today there are about 130 Ditidaht people living at balaats’adt. Although Joe and Frances Edgar have lived at Malachan since the late 1940s, it is only since the 1960s that a lot of people have lived here. Among the first people to move from Clo-oose and Whyac up to Malachan in the 1960s were Stanley Chester and the late Webster Thompson.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 12

Ilhuu is the name of “Il-clo” Indian Reserve No. 12. It is located on the west side of Nitinat Lake, near its upper end.

This was a place where the Ditidaht people used to stay during the fishing season. Many years ago, some people would also spend the winter here. There were five houses at ilhuu when this 77-acre reserve was surveyed in 1893; there were also five houses here in 1914. Today there is one house here.

A long time ago, the Ditidaht people built a special “underwater fence” in the bay at the northern end of ilhuu. This fence was made of small trees and was constructed so that the tops of these trees were just under the water’s surface. If enemy canoes tried to come here, they would be stopped by this fence.

The secret ceremonies of the tluukwaali, known as the “Blackface Society” (or the “Wolf Dance”) used to be danced here at ilhuu. This was many years ago. In these ceremonies, humans dress in wolf skins and pretend they are wolves. It is a very sacred ceremony to our people who belong to this secret society.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 13

The Ditidaht name for “Opat-se-ah” Indian Reserve No. 13 is . It is located at the head end of Nitinat Lake and on the east side of the Nitinat River mouth.

There were two houses at up’aachi7a when this 71-acre reserve was surveyed in 1892. In the 1920s, there were four houses here.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 14

Wak’it-tsaas means ‘frog on the side.’ This is the name of “Wok-it-sas” Indian Reserve No. 14. It is located on the west side of the lower Nitinat River. Today, a lot of people know wak’it-tsaas as “Red Rock.

A long time ago, wak’it-tsaas was a place where our people caught and dried salmon in the fall. They used a fish weir and trap to catch fish here. There was one house at “Wok-it-sas” when the 40-acre reserve was surveyed in 1892. At that time there was also a fish weir and trap here. In 1914, there were three houses here and the fish trap was still in use.

Among those people who used to have houses at wak’it-tsaas were Peter Dick, George Thompson, and Old Jimmy Chester.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 15

This reserve is called shuuch’abisapuu which means ‘place of trees.’ It is known as “Chu-chum-mis-a-po” Indian Reserve No. 15 and is located on the east side of the Nitinat River where Jasper Creek enters the Nitinat. There is a bridge here at the lower intersection of the one-way road.

Shuuch’abisapuu was another area where the Ditidaht caught and dried salmon in the fall. It was an especially good place for coho. The Ditidaht used a fish weir and trap here in past years, but gaffs and spears were used in more recent times. There was one house at “Chu-chum-mis-a-po” and also a fish weir here when this 92-acre reserve was surveyed in 1893. In 1914 there was also one house here. The Shaw family used to have a house here.

Nitinaht Indian Reserve No. 16

The Ditidaht name of this place is ts’aa7ukw which means ‘creek on the side.’ It is known as “Sa-ouk” Indian Reserve No. 16. Ts’aa7ukw is located on the west side of the Nitinat River, where Parker Creek enters the Nitinat.

This was another place where the Ditidaht people caught and dried salmon in the fall. There were four houses at “Sa-ouk” when this 160-acre reserve was surveyed in 1893 and there were two houses here in 1914. Among those who used to have houses here were Harry Joseph and George Thompson’s father.

Ts’aa7ukw was as far as it was possible to go up the Nitinat River by canoe. Just past here there is a waterfall. The water become very rough and not even the salmon can get past it. The people had to leave their canoes right here and walk on the trail to get to Cowichan Lake.

Our people

The present Ditidaht Nation is an alliance of at least ten “local groups” each consisting of a group of people occupying a specific geographical area and centered around chiefs and their families. The local group took its name from the name of its main village’s location. It is likely that these groups were more independent long before the White people came to our shores, but during the time since our history has been recorded in documents, we have been viewed as one people, with one common territory, and one name by which we are all known today. We are Ditidaht, or as we say in our own language, diitiid7aa7tx. Some of us prefer the name da7uu7aa7tx, the name of the original Nitinat Lake people. But today we are best known as the Ditidaht.

Our name for ourselves means ‘people of diitiida,’ as the suffix -aa7tx means ‘people.’ Therefore, when we refer to the names of the individual groups comprising our Ditidaht Nation, we use the name of their original village, plus the suffix ‘people.’ For example, these are the names of some of the original local groups that form the present Ditidaht Nation, and the location of their main village:

tsakkawis7aa7tx ‘people of taskkawis.’

Tsakkawis is located about 500 feet west of the mouth of an un-named creek located west of the Klanawa River and east of the Darling River. Although the Government agreed to our request that tsakkawis be set aside as an Indian Reserve, this was never done.

tl’aadiiw7aa7tx ‘people of tl’aadiiwa.’

Tl’aadiiwa, anglicized as “Klanawa,” is the name of an area at the mouth of the Klanawa River, and of the river, itself.

tsuxwkwaad7aa7tx ‘people of tsuxwkwaada.’

This site was set aside as “Tsuquanah” Indian Reserve No. 2. It is located on the ocean west from the entrance to Nitinat Narrows.

da7uu7aa7tx ‘people of da7uuw7aa.’

The term da7uuw7aa is used to refer to an area also known as “Iktuksasuk” (anglicized from hitats’aasak) Indian Reserve No. 7 located at the lower end of Nitinat Lake. This Indian Reserve is known locally as “the Flats.” Some Ditidaht people use the word da7uuw7aa to refer also to the entire Nitinat Lake area.

waayaa7ak7aa7tx ‘people of waayaa.’

Known locally as “Nitinat,” waayaa (or waayaa7ak, anglicized as “Whyac”) was one of the largest Ditidaht villages in historic times. Wyah Indian Reserve 3 was occupied until the 1960s.

tluu7uus7aa7tx ‘people of tluu7uus.’

The name tluu7uus refers to a Ditidaht village site and halibut fishing station situated on the ocean shore in Clo-oose Bay. It is known also as “Clo-oose” (anglicized from tluu7uus) Indian Reserve No. 4.

wawaax7adi7s7aa7tx ‘people of wawaax7adi7s.’

Wawaax7adi7s is the name of a beach located northwest from Carmanah Point.

kwaabaaduw7aa7tx ‘people of kwaabaaduwa7.’

This name applies to the area now known as Carmanah Indian Reserve No. 6, located northwest from the mouth of the Carmanah Creek

These are only a few of our ancestors’ villages. These are places where they maintained large cedar plank houses that provided shelter and warmth during the wet and dreary westcoast winters. They also had camps situated throughout our territory where they stayed while fishing, hunting, gathering seafoods and wild plants, or making canoes. Living well in Ditidaht territory required a thorough knowledge of the location of resources and the times of their availability. Such a strategy developed over many, many years. Our ancestors knew where to go at each particular time of year. We have marked the location of each of these named places on maps and have recorded the use and history of each place. In this way we have identified about 250 Ditidaht place names.

Our language

The Ditidaht and the Pacheenaht people speak closely-related dialects of a language called Nitinaht or “Ditidaht.” We are proud of this distinctive language that separates us from our neighbours. Our language, Ditidaht, is one of three closely-related languages (Nitinaht, Makah, and Westcoast) forming the South Wakashan sub-group of the Wakashan Language Family. Our American relatives across the Strait of Juan de Fuca around Neah Bay speak Makah, and our neighbours living northwest from Pacheena Point speak Westcoast (also called “Nuu-chah-nulh,” but formerly called “Nootka”).

The Nitinaht and Makah languages are much more closely related to each other than they are to Westcoast.

Formerly, Westcoast speakers lived along the west coast of Vancouver Island between Cape Cook and Pachena Point; speakers of Nitinaht lived along the coast (including the area up the Nitinat drainage and Cowichan Lake) between Pachena Point and Point No Point; and Makah speakers lived along the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, between the Hoko River and Cape Alava. Nowadays, all of these groups are concentrated in several main villages.

Traditions

Property

Our chiefs, known as chaabat’, held rights to the fish, roots, and other food resources within our territory. The chiefs also held the weir trap prerogatives on the major salmon streams. So strict were these property rights that poachers were killed for serious infractions, although theft of plant foods would result only in confiscation of the illegal harvest. Some high-status people held rights to certain salmon-harpooning sites or rocks where particularly good seafood could be harvested.

Ditidaht families also held rights to intangible property called tupaat. Tupaat is an hereditary privilege or prerogative that often refers to ceremonial privileges that were frequently part of marriage dowries. Ditidaht tupaat consisted of songs, dances, games, history, crests and gear that continue to be displayed at our feasts. Tupaat are still recognized and celebrated today.